CELIAC DISEASE OVERVIEW

Celiac disease is a condition in which the

immune system responds abnormally to a protein

called gluten, which then leads to damage to the

lining of the small intestine. Gluten is found

in wheat, rye, barley, and a multitude of

prepared foods. Celiac disease is also known as

gluten-sensitive enteropathy and celiac sprue.

The small intestine is responsible for absorbing

food and nutrients. Thus, damage to the lining

of the small intestines can lead to difficulty

absorbing important nutrients; this problem is

referred to as malabsorption. Although celiac

disease cannot be cured, avoiding gluten usually

stops the damage to the intestinal lining and

the malabsorption that results. Celiac disease

can occur in people of any age and it affects

both genders.

CELIAC DISEASE

SYMPTOMS

The symptoms of celiac

disease vary from one person to another. In its

mildest form, there may be no symptoms

whatsoever. However, even if you have no

symptoms, you may not be absorbing nutrients

adequately, which can be detected with blood

tests. As an example, you can develop a low

blood count as a result of decreased iron

absorption.

Some people have bothersome

symptoms of celiac disease, including diarrhea,

weight loss, abdominal discomfort, excessive

gas, and other signs and symptoms caused by

vitamin and nutrient deficiencies.

Some

conditions are more common in people with celiac

disease, including:

- Osteopenia or

osteoporosis (weakening of the bones)

- Iron

deficiency anemia (low blood count due to lack

of iron)

- Diabetes mellitus (type I or

so-called juvenile onset diabetes mellitus)

-

Thyroid problems (usually hypothyroidism, an

underactive thyroid)

- A skin disease called

dermatitis herpetiformis

- Nervous system

disorders

- Liver disease

CELIAC DISEASE CAUSES

It is not

clear what causes celiac disease. A combination

of environmental and genetic factors is

important. Celiac disease occurs widely in

Europe, North and South Americas, Australia,

North Africa, the Middle East, and in South

Asia.

Celiac disease occurs rarely in

people from other parts of Asia or sub-Saharan

Africa.

CELIAC DISEASE DIAGNOSIS

Celiac disease can be difficult to diagnose

because the signs and symptoms are similar to

other conditions. Fortunately, testing is

available that can easily distinguish untreated

celiac disease from other disorders.

Blood tests - A blood test can

determine the blood level of antibodies

(proteins) that become elevated in people with

celiac disease. Over 95 percent of people with

untreated celiac disease have elevated antibody

levels (called IgA tissue transglutaminase, or

IgA tTG), while these levels are rarely elevated

in those without celiac disease. Levels of other

antibodies (called IgA or IgG deamidated gliadin

peptide) are also usually abnormally high in

untreated celiac disease. Before having these

tests, it is important to continue eating a

normal diet, including foods that contain

gluten. Avoiding or eliminating gluten could

cause the antibody levels to fall to normal,

delaying the diagnosis.

Small

intestine biopsy - If

your blood test is positive, the diagnosis must

be confirmed by examining a small sample of the

intestinal lining with a microscope. The sample

(called a biopsy) is usually collected during an

upper endoscopy, a test that involves swallowing

a small flexible instrument with a camera. The

camera allows a physician to examine the upper

part of the gastrointestinal system and remove a

small piece (biopsy) of the small intestine. The

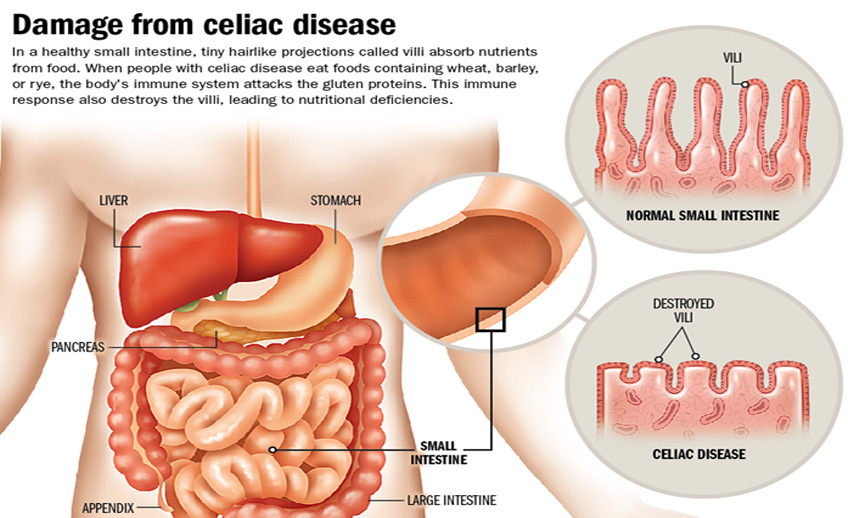

biopsy is not painful. In people with celiac

disease, the lining of the small intestine has a

characteristic appearance when viewed with a

microscope. Normally, the lining has distinct

finger-like structures, which are called villi.

Villi allow the small intestine to absorb

nutrients. The villi become flattened in people

with celiac disease. Once you stop eating

gluten, the villi can resume a normal growth

pattern. More than 70 percent of people begin to

feel better within two weeks

after stopping

gluten.

One way to determine if

the gluten-free diet is working is to monitor

the levels of antibodies in your blood. If your

levels decline on a gluten-free diet, this

usually indicates that the diet has been

effective.

"Potential" celiac

disease - People with a positive IgA

endomysial antibody test and/or a positive IgA-tTG

test and a normal small bowel biopsy are

considered to have potential celiac disease.

People with potential celiac disease are not

usually advised to eat a gluten-free diet.

However, ongoing monitoring (with a blood test)

is recommended and a repeat biopsy may be needed

if you develop symptoms. Biopsies should be

taken from several areas in the bowel since the

abnormality can be patchy.

"Silent" celiac disease - If you have a

positive blood test for celiac disease and an

abnormal small bowel biopsy, but you have no

other symptoms of celiac disease, you are said

to have "silent" celiac disease. It is not clear

if people with silent celiac disease should eat

a gluten-free diet. Blood tests for

malabsorption are recommended, and a gluten-free

diet may be needed if you have evidence of

malabsorption.

Testing for

malabsorption - You should be tested

for nutritional deficiencies if your blood test

or bowel biopsy indicates celiac disease. Common

tests include measurement of iron, folic acid,

or vitamin B12, and vitamin D. You may have

other tests if you have signs of mineral or fat

deficiency, such as changes in taste or smell,

poor appetite, changes in your nails, hair, or

skin, or diarrhea.

Other tests

- Other standard tests include a CBC (complete

blood count), lipid levels (total cholesterol,

HDL, LDL, and triglycerides), and thyroid

levels. Once your celiac antibody levels return

to normal, you should have a repeat test once

per year.

Many clinicians recommend a test for bone

loss 12 months after beginning a gluten-free

diet. One method involves using a bone density

(DEXA) scan to measures your bone density. The

test is not painful and is similar to having an

x-ray. If you have significant bone loss, you

may need calcium and vitamin D supplements, an

exercise program, and possibly a medicine to

stop bone loss and encourage new bone growth.

CELIAC DISEASE COMPLICATIONS

Nonresponsive celiac disease -

Approximately 10 percent of people with celiac

disease experience ongoing symptoms despite

adhering to a gluten-free diet. There are many

causes, including other food intolerances such

as fructose (or other fermentable carbohydrate)

malabsorption, food allergies, bacterial

overgrowth in the small intestine or conditions

such as microscopic colitis, irritable bowel

syndrome, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, or

refractory celiac disease. However, the most

common cause is ongoing, often inadvertent,

gluten ingestion. Thus, an essential first step

in evaluating nonresponsive celiac disease is

consultation with an experienced celiac

dietitian.

Refractory celiac

disease - A small percentage of people

develop intestinal symptoms that do not improve

despite use of a strict gluten-free diet. In

other cases, intestinal symptoms initially

improve with dietary changes but then return.

People who have these problems may have

refractory celiac disease. The cause of this

problem is not known. Treatment involves

medications that suppress the immune system's

abnormal response (eg,

steroids). Treatment is important

because

people with untreated celiac disease can develop

anemia, bone loss, and other consequences of

malabsorption.

Ulcerative

jejunitis - People with refractory

celiac disease who do not improve with steroids

(glucocorticoids) may have a condition known as

ulcerative jejunitis. This condition causes the

small intestine to develop multiple ulcers that

do not

heal; other symptoms may include a

lack of appetite, weight loss, abdominal pain,

diarrhea, and fever. This condition can be

difficult to treat. Treatment may require

surgery to remove the ulcerated area.

Lymphoma - Cancer of the

intestinal lymph system (lymphoma) is an

uncommon complication of celiac disease.

Avoiding gluten can usually prevent this

complication.

Skin conditions - Celiac

disease is associated with a number of skin

disorders, of which dermatitis herpetiformis is

the most common. Dermatitis herpetiformis is

characterized by intensely itchy, raised,

fluid-filled areas on the skin, usually located

on the elbows, knees, buttocks, lower back,

face, neck, trunk, and occasionally within the

mouth.

The most bothersome symptoms are

itching and burning. This feeling is quickly

relieved when the blister ruptures. Scratching

causes the area to rupture, dry up, and leave an

area of darkened skin and scarring. The

condition will improve after eliminating gluten

from the diet, although it may take several

weeks to see significant improvement. In the

meantime, an oral medication called dapsone may

be recommended. Dapsone relieves the itching but

does not heal the lining of the small intestine;

thus, the gluten-free diet is the most effective

therapy for those with dermatitis herpetiformis.

CELIAC DISEASE TREATMENT

Gluten-free diet - The cornerstone of treatment

for celiac disease is complete elimination of

gluten from the diet for life. Gluten is the

group of proteins found in wheat, rye, and

barley that are toxic to those with celiac

disease. Gluten is not only contained in these

most commonly consumed grains in the Western

world, but is also hidden as an ingredient in a

large number of prepared foods as well as

medications and supplements. Maintaining a

gluten-free diet can be a challenging task that

may require major lifestyle adjustments. Strict

gluten avoidance is recommended since even small

amounts can aggravate the disease. It is

important to avoid both eating gluten and being

exposed to flour particles in the air.

Get help from a dietitian - An

experienced celiac dietitian can help you to

learn how to eat a gluten-free diet, what foods

to avoid, and what foods to add for a

nutritionally balanced diet. Your dietitian can

also recommend gluten-free vitamin/mineral and

other supplements, as needed. Your celiac

dietitian can also educate you on shopping, food

preparation, and lifestyle resources. Excellent

resources are also available from celiac medical

centers, organizations, and support groups.

Fortunately, life on a gluten-free diet becomes

increasingly easier each year due to the rising

popularity of gluten-free foods among those with

celiac disease, nonceliac gluten sensitivity,

and wheat allergies. Excellent gluten-free

substitute foods are now widely available in

supermarkets, health food stores, and online.

General tips

Avoid foods

containing wheat, rye, barley, malt, brewer's

yeast, oats (unless pure, uncontaminated,

labeled gluten-free oats), and yeast extract and

autolyzed yeast extract (unless the source is

identified as gluten-free). "Malt" means "barley

malt" unless another grain source is named, such

as "corn malt." The US Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) and the United States

Department of Agriculture have different

regulations around gluten-free food labeling.

According to the FDA regulations issued in

August 2013, foods with "gluten-free" labeling

must contain less than 20 parts per million

(ppm) of gluten. The following table has a list

of prepared foods that contain or may contain

gluten. Naturally gluten-free foods include

rice, wild rice, corn, potato, and other foods

listed in the table. These foods may be

contaminated with wheat, barley, or rye. Choose

labeled gluten-free versions of these products.

Exceptions are fresh corn, fresh potatoes, nuts

and seeds in their shells, dried lentils

(legumes), and dried beans. These foods may not

be labeled gluten-free but are still considered

safe to eat. Pick through and rinse dried

legumes and dried beans.

If a food is

regulated by the FDA and is not labeled

gluten-free (such as prepared foods and

condiments), read the ingredients list and

"contains" statement carefully. The word "wheat"

will be included if the product is FDA regulated

and contains wheat protein. If you do not see

any of the following words on the label of an

FDA-regulated food (wheat, rye, barley, malt,

brewer's yeast, oats, yeast extract, and

autolyzed yeast extract) then the product is

unlikely to include any gluten-containing

ingredients. However, the Food Allergen Consumer

Protection Act pertains to ingredients only. It

does not cover wheat protein that may be in a

product unintentionally due to cross-contact.

Distilled alcoholic beverages and vinegars, as

well as wine, are gluten-free unless

gluten-containing flavorings are added after

production. However, malt beverages, including

beer, are not considered gluten-free. There are

specially produced beers that do not use malted

barley that are labeled gluten-free and can be

consumed on a gluten-free diet. Please note that

malt vinegar is not gluten-free.

You may

not tolerate dairy products initially while your

intestines are healing. If you tolerated lactose

before your diagnosis, you may be able to

tolerate it again after the intestine heals. In

the meantime, choose lactose-reduced or

lactose-free products if your symptoms are

worsened by dairy products. Choose labeled

gluten-free, dairy-free alternatives, such as

rice, soy, or nut (almond, hazelnut) beverages

that are enriched with calcium and vitamin D.

Keep in mind that gluten-free rice and nut milks

have minimal protein per serving compared with

cow's or soy milk. Gluten-free lactase enzyme

supplements are also available, which may help

you to tolerate foods that contain lactose.

Discuss your need for calcium and vitamin D

supplements with your healthcare provider or

dietitian. A small percentage of people with

celiac disease cannot tolerate gluten-free oats

for several reasons. If you choose to eat

gluten-free oats, first talk to your doctor who

can check your IgA-tTG level and monitor any

symptoms. In addition, choose only specially

produced gluten-free oats. Limit your intake of

gluten-free oats to no more than 50 grams

(approximately 1/2 cup dry rolled oats or 1/4

cup dry steel-cut oats) per day. If tolerated,

you may be able to discuss eating more than 1/2

cup per day under the supervision of your

doctor.

Is gluten avoidance

really necessary? - People who have no

symptoms of celiac disease often find it

difficult to follow a strict gluten-free diet.

Indeed, some healthcare providers have

questioned the need for a gluten-free diet in

this group. However, certain factors support a

gluten-free diet, even in those without

symptoms: Strictly following a gluten-free diet

sometimes helps you to feel more energetic and

have an improved sense of health and wellbeing.

Some people with celiac disease have vitamin or

nutrient deficiencies that do not cause them to

feel ill, such as anemia due to iron deficiency

or bone loss due to vitamin D deficiency.

However, these deficiencies can cause problems

over the long term.

Untreated celiac

disease can increase the risk of developing

certain types of gastrointestinal cancer. This

risk can be reduced by eating a gluten-free

diet.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE FAMILY

Eliminating gluten requires a major lifestyle

change for you as well as your family. However,

with time and practice, it will be easier to

know which foods, medications, supplements, and

oral care products contain gluten and what

alternatives are available. Although eating out

can be challenging initially, restaurants have

become increasingly interested in serving people

with celiac disease by offering a gluten-free

menu or ingredient substitutions. Families also

need to be aware of their increased risk of

celiac disease. Thus, your first-degree

relatives (parents, brothers, sisters, children)

should consider being tested, especially if

anyone has signs or symptoms of the condition.

Testing is typically done with a blood antibody

test, as described above.